- It is spread through the air and contact with contaminated surfaces.

- It is extremely infectious—much more so than COVID or flu—with up to 9 out of 10 susceptible (unvaccinated) individuals developing disease following exposure to an infected person, through coughs, sneezes, or even just being in the same room.

- Measles complications lead to hospitalization in 1 in 5, pneumonia in 1 in 20, and brain infection (encephalitis) in 1 in 1000 cases.

- While children are most commonly affected, unvaccinated adults, pregnant people, and those with compromised immune systems are at increased risk.

- The measles vaccine is administered in the form of a combination vaccine known as MMR, which covers measles, mumps, and rubella.

- In the U.S., children typically receive one dose at 12 months of age, and a second dose at 4-6 years.

- It is one of the safest and most effective vaccines we have: 93% effective after one dose, and 97% effective after the full two-dose series. Protection is considered lifelong, and boosters are not needed.

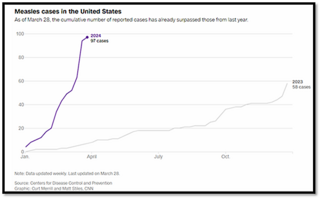

Why is measles on the rise?

Measles typically enters the U.S. through travelers who have been infected in other countries, including U.S. travelers returning from abroad. Outbreaks (three or more linked cases) occur when an imported case comes in contact with unvaccinated individuals. Outbreaks are more likely when the rate of overall vaccination in a community falls below the level required to provide herd immunity—estimated at 95% for measles.

- The COVID pandemic disrupted international immunization programs, leading to outbreaks around the world, including in common destinations like the United Kingdom.

- The rise in vaccine hesitancy in the U.S. has led to declines in the vaccination rates of young children.

- Vaccine coverage of U.S. kindergarten children has fallen from 95.2% in 2019-2020 to 93.1% in 2022-2023. A number of states have rates below 90%.

How does this impact me?

While no measles cases have been identified in Connecticut so far in 2024, it is possible for measles to be introduced to New Haven or to the Yale community. Many members of the Yale community, including international students and scholars, travel to and from parts of the world where measles may be active.

What can we do to reduce the risk of a measles outbreak?

- Yale protects the community by requiring that all incoming students, and all healthcare workers and healthcare trainees, document that they are vaccinated or immune.

- If you have small children, ensure that they receive their recommended immunizations on time to protect them and to help our communities maintain herd immunity protections.

- If you are planning international travel, be aware of the measles risk in your destination, and check on your and your family’s vaccine status.

- Infants under 12 months who are traveling should receive an early dose between 6 and 11 months, followed by the standard two-dose series (at 12-15 months and then 4-6 years).

- Children over 12 months should receive two doses at least 28 days apart.

- Contact your healthcare provider if your child becomes ill following travel.

- Most adults were fully vaccinated as children and do not require additional testing or vaccination. Check your immunization records, especially if you plan to travel.

- See this FAQ from the CDC for more useful information.

- Americans born before 1957 are considered immune.

- If you did not receive routine childhood vaccinations, especially if you were born outside the U.S., speak to your healthcare provider.

While the risk of a serious outbreak of measles is low, it is preventable if we remain aware, alert, and prepared.

In health,

Madeline Wilson, MD

Chief Campus Health Officer